3 . Prime Directive Ignorance

A retrospective Facilitation Antipattern

By Aino Vonge Corry

SUMMARY

Retrospectives are for finding ways to improve the team’s work together, not for finding a scapegoat. However, it is natural for us to want to find a scapegoat, so it takes a conscious decision not to do it.

This is about a retrospective Facilitation Antipattern in which the team members ignore the Prime Directive because they find it ridiculous, and the facilitator reminds them how important this mindset is for a successful retrospective.

Context

Sarah is the Scrum Master of a small team and facilitates most of the retrospectives. For this retrospective, Sarah has done her homework. Not only has she read Agile Retrospectives: Making Good Teams Great (Larsen & Derby 2006), but she has also read Project Retrospectives: A Handbook for Team Reviews (Kerth 2001).

She discovers that there is a lot to think about when planning and facilitating a retrospective, but luckily, Larsen and Derby’s book has made planning an easier task by providing suggestions for entire retrospective agendas.

With a planned retrospective ahead of her, Sarah is excited and a little bit worried. The thing she most worries about is how to present Norm Kerth’s Prime Directive to the developers, since she believes they might find it ridiculous.

In the end, she decided to drop it!

Prime Directive

The last sprint had been a disaster with everyone working overtime and no one feeling good about the result. Well, almost everyone worked overtime – Peter had not. He went home every day at the usual time; he would sneak out thinking nobody noticed him and arrive late in the mornings.

There had been some grousing about this by the water cooler and in the corners, and it was secretly decided that the retrospective was the place to deal with. Sarah and Peter were the only people who did not know of this plan.

At the retrospective, they looked at the data – the regression tests and the feedback from the demo with the users – and they put Post-it Notes on a timeline to share their experiences.

It was obvious that Peter was being blamed for the team’s overall dissatisfaction. There were Post-it Notes with his name on the board, and he became even more silent than he usually was.

Since there were so many notes, Sarah decided to read them all out herself, thinking it would take too long if they all had to read a portion. But there was also another reason Sarah chose to read the notes: as she read them aloud, she tried to avoid the Post-it Notes with Peter’s name on them.

Everybody had already seen the notes, though, so Sarah’s effort to shield Peter was in vain.

Peter left the retrospective in complete silence, and the rest of the team members felt unsure about what to do next. They had hoped that he would apologize to them or explain his behavior, but they had never really given him a chance to enter the discussions.

General Context

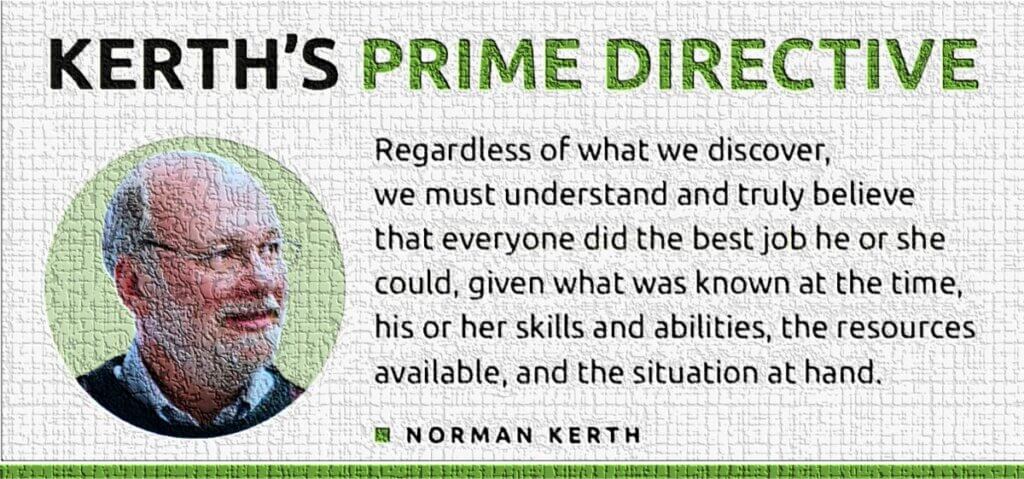

Norm Kerth was the first to write about retrospectives, and he coined the term after they had been called postmortems for some time.

He wrote the Prime Directive mentioned above, and it has been the center of much discussion in the IT community:

Can we really, regardless of what we discover, understand and truly believe that everyone did the best job they could? Even if we made allowances for what they knew at the time, their skills and abilities, the resources available, and the situation at hand?

At the end of a project, everyone knows so much more than at the beginning. Naturally, we look back on decisions and actions we wish we could do over. This is wisdom to be celebrated, not judged and used to embarrass people.

Adhering to the Prime Directive, we want to combat confirmation bias in retrospectives. If we are filtering information to accept data only that supports our preconceived opinions, we are missing a chance to learn.

The problem is that it feels awkward to follow this directive, because it is hard to really and truly believe that everybody else is doing their best when you know they are slacking or being lazy.

One of the reasons that we find this hard is explained by the fundamental attribution error described in The Intuitive Psychologist and His Shortcomings: Distortions in the Attribution Process (Ross 1977). This error explains how we attribute flaws in the behavior of other people to internal traits, such as laziness, stupidity, and so on, instead of attributing it to the circumstances this person is in.

As an example, if you are late for a meeting, you might attribute your tardiness to the problems you had with getting the kids to school or to the bus being late. But if someone else is late to the meeting, you might roll your eyes and think he or she is an irresponsible person, according to the fundamental attribution error.

Antipattern Solution (what normally happens)

Just forget the Prime Directive. It is too touchy-feely for a logical bunch of programmers. As simple as that. Ignore it. Or, recite it with a mocking smile on your face, signaling that everybody can just forget about it. Go ahead with the retrospective and get on with the data collection.

Consequences (from applying the antipattern solution)

Your retrospective will now be like any other review session, where we, like most people, are interested only in finding a scapegoat to direct blame away from ourselves.

Scapegoating is a common non-solution to problems, and you probably experienced it in childhood when your parents asked you and your siblings, “Who started it?” or “Who broke the vase?”

The consequence could be that participants bring all their assumptions and negative expectations to the retrospective instead of anticipating a chance to share and learn. They do not really listen to what others are saying because they already believe they know whom to blame. The retrospective can easily become a blaming and shaming session, where the people being blamed are afraid to share and in the end refuse to attend the retrospectives because they become too painful.

Symptoms (what you see from the distance)

Team members are afraid to go to the retrospectives when something has gone wrong. They are not eager to learn to become wiser but instead are afraid of what might happen at the retrospective. People arrive in a defensive mood, armed with angry counterarguments to the attacks they expect and unwilling to explore the issues together.

Refactored Solution (what you could do instead)

Bring the directive to each retrospective, and start with it. I have found that some groups react negatively to the wording of the Prime Directive, and in those cases, I reword it but maintain the core idea that we should all look for the problems in the system, not in the people.

The Prime Directive should be seen as a way to think about, a state of mind to enter when you walk into a retrospective. Having a retrospective is a team thing, so you should think of everyone as part of the team, or as part of a system, and find ways to improve that system. If you start out by thinking they purposely have not done their best, you will not have a fruitful retrospective.

Had Sarah’s team entered the retrospective thinking about the Prime Directive, they might have learned that Peter’s wife was terminally ill, and that this was the reason he was not pulling his weight at work.

Maybe Peter would have shared, had he felt secure and safe at the retrospective. Then they might have found something that Peter could do together with someone else or given him less work for a period while he figured out what would happen to him emotionally and financially as he went through this very difficult and painful part of his life.

It could also be that Peter was uncomfortable sharing this at a retrospective and needed a more private setting to share this personal information and its consequences.

In any case, accepting that Peter was not to blame and acknowledging that the way the team worked together and communicated was faulty would have been a more likely and positive result had they focused on the mindset proposed by the Prime Directive.

Personal Anecdotes

Many years ago, in a retrospective not facilitated by me but for my team, something very sad happened. During the data gathering, one name was singled out on the board with some negative comments. The facilitator did not stop it, and soon a whole swarm of Post-it Notes about that person filled the board.

Not surprisingly, this experience was unpleasant for the person in question, but it was about a behavior that everyone was tired of and that affected our work together. The facilitator allowed us to start talking about the different Post-it Notes on the board, what they meant, and the stories behind them.

The person in question started defending himself, but in the end, he stormed out of the room. We never got anywhere near understanding what actually created the behavior or what we could do collectively to help this person or at least learn to work around it.

The time spent on that retrospective was more than wasted––it harmed us for good.

Another time, I witnessed something touching concerning a young man who had recently joined the team. I could see from the start of the retrospective that he felt really bad about something. It turned out that he thought he had done a disastrous job of working on the front-end of the system, taking too long, making mistakes.

But the rest of the team turned to him, when they realized how he felt, and gave him a veritable love-storm. They let him know that of course he needed time to learn about the system. In addition, they told him that because of his work, they had learned which parts of the system needed more documentation or even a rewrite. The young man was so happy and relieved, it almost brought a tear to my eye!

Online Aspect

If the retrospective is conducted online, you can add the Prime Directive to the email that is attached to the calendar invitation.

You can also have the Prime Directive on a poster behind your head as a constant reminder of it.

You might also be able to send messages directly to the people you think are not following the directive to remind them about it without making them loose face in front of everyone else.

I am Aino Vonge Corry and these are my agile-thoughts

2021 © Aarhus, Middle Jutland, DENMARK by Aino Vonge Corry

Aino Vonge Corry (born 1971 in Aarhus, Denmark) likes to sing, run and to make agile embroideries (in the sense that they are done when they are done, not necessarily with all the features planned from day one).

Aino has lived in Stockholm, Lund, and Cambridge, but she is now back in Aarhus, Denmark, where she lives with her family, and a growing collection of plush cephalopods.

USEFUL? You can share it!