4 . Creating Coherent “Explore Spaces” (I)

How Constraints Can Enable a New Thinking and Practice

By Sonja Blignaut

I have written before about the need to embrace messy coherence or in more technical terms, coherent heterogeneity, a term I first encountered in the work of Dave Snowden.

While most intuitively understand this need, how to achieve it practically remains elusive. We are emerging from a time where alignment and efficiency were pursued like the holy grail. The shift towards embracing messiness and diversity seems almost impossible, especially to leaders and managers who equate competence with control.

Yet, I encounter similar questions in almost every conversation: How do we distribute decision-making and authority? How do we build strong coherent cultures AND nurture diversity and adaptation? How do we maintain momentum when we are not able to plan and set clear goals? How do we organise and structure ourselves in ways that enable adaptation?

There is no recipe for achieving this, however I think a possible key to finding our way lies in understanding how to enable coherence.

Embracing messy coherence requires us to let go of long-held assumptions of a world where stability, certainty and predictability are the norm.

In this world, we were taught to use linear, deterministic management methods and tools and also that alignment to shared goals and values is key to success.

The COVID19 pandemic and climate change, among others, have made us realize that we do indeed inhabit a complex and entangled world, one that is unpredictable. Like a deer in the headlights, we easily become paralyzed when dealing with uncertainty, which is the last thing we can afford.

It is now necessary, for a post-pandemic world, to move forward rather than reverting back to the previous practices that failed us during these recent events.

In Abraham Lincoln’s words, we need to “think anew and act anew”

The field of complexity, called by some the “science of uncertainty,” offers us a new lens or worldview when viewing social systems. When we shift from seeing human systems as machines and individuals as controllable and predictable cogs, to viewing them as complex adaptive systems through the lens of complexity science, new possibilities become evident.

In the past, we have relied on ordered systems due to them being predictable and controllable.

These closed systems are easily managed through planning, goal setting, measuring, and feedback mechanisms that control the system’s outcomes. Closed systems operate using causal relationships (i.e., control the system’s outcome or ideal future state, B, by altering its input, A). I call this A to B thinking. And it is one of the primary reasons for the focus on alignment I described earlier.

This kind of linear, deterministic thinking has long been taught in management programs. Today, however, decision-makers are increasingly finding themselves in entirely uncharted and dynamic territories, what Ann Pendleton-Jullian aptly calls a white-water world.

There are no road maps leading us to where we are going today. Alignment in this world creates a focus that is too narrow, we need to create coherent explore spaces with broader horizons and more diverse options.

So how do we do this?

Before we dive into that, I need to define three foundational terms and ideas that I believe are critical and form the basis for the framework I will later describe.

a) Constraints: Limits AND Enablers

“…the notion of a constraint is not a negative one. It is not something which merely limits possibilities, constraints are also enabling. By eliminating certain possibilities, others are introduced” –Cilliers, 2001.

While most people view constraints as being primarily restrictive, it is important to understand constraints can also be enabling, i.e., they create opportunity for action, and may even need to be understood in multiple senses at the same time.

Humans have learned to create order through constraints. For example, without a demarcated playing field, defined team roles, and rules that govern the game, we would not have team sports like rugby or hockey. Without traffic conventions which shape how we drive as well as our expectations of other drivers, there would be chaos on our roads.

Therefore, constraints do not only remove or limit options but also create or enable order and new possibilities.

b) Invitations to Act Through “Affordances”

To better understand options and possibilities, I need to introduce the concept of an affordance.

“Affordances are invitations to act within an environment; however, they are not properties of the environment per se, but rather a property of the Environment-Agent-System” –Lee, Bootsma, Frost, Land, Regan and Gray, 2009. EAS.

In the right context, many surfaces might afford us the possibility of being seated. Chairs, logs, low walls … all invite the action of sitting.

They also have the potential to shape not only individual action, but also social interactions. Arranging chairs in a row affords different social interactions compared to arranging chairs in a circle. If I want a group to interact and engage in a more lively or intimate way, I can invite their participation by changing how I design or constrain the environment. I do not have to tell them to act in a certain way, the environment invites or affords that behaviour.

This is important, because if we do not carefully consider the environment we put employees in, the inherent constraints of the environment may create a disabling one.

For example, while organizations may try to create collaborative work environments, the inhibiting constraints introduced by performance management systems, predetermined targets and incentives may prevent collaboration from occurring organically. It becomes a synthetic form of collaboration, made up.

Affordances and constraints play a key role in innovation and adaptation. Constraints create affordances or opportunities for action. Therefore, perceiving affordances in dynamic environments is key to innovation.

Think for example of a gap that opens up on a rugby or hockey field and the ability to judge whether it affords the action of running through it or not. Or recognising different or new affordances in the same environment, i.e., the ability to repurpose an object or space.

We experienced this recently when the resource constraints created by the COVID19 pandemic created the conditions for this kind of innovation (e.g., the repurposing of dive masks into respirators).

c) Boundaries & Containment

“A Safe Environment for Exploration.”

Boundaries also function as constraints. Knowing where the boundaries are can help people to feel safe to explore, make decisions and embrace change.

Unbounded spaces can feel overwhelming, confusing, and unsafe. If we do not know where our boundaries are, we do not know when we cross them. So very often we choose to play it safe and just do what we are told.

Similarly, over-constrained environments can stifle creativity and engagement. To foster cultures able to explore and adapt, we need to create environments that have adequate and appropriate constraints in place.

Now that we have explained some of the core concepts, let’s bring it all together.

WaysFinding in complexity

At the beginning, I mentioned some questions:

- How do we distribute decision-making and authority?

- How do we build strong coherent cultures AND nurture diversity and adaptation?

- How do we maintain momentum when we are not able to plan and set clear goals?

- How do we organise and structure ourselves in ways that enable adaptation?

While working with clients who are struggling with these questions, I have been exploring how to enable these safely bounded search or exploration spaces where an interplay of different constraints enable local autonomy and diversity, while maintaining overall strategic or identity coherence.

In this exploration, I have been inspired by various artists, jazz musicians, sports teams, and ancient mariners. I have also borrowed thoughts from a number of theorists/philosophers (Dave Snowden, Paul Cilliers, Alicia Juarrero, Mary Uhl-Bien, & Ann Pendleton-Jullian). Concepts such as constraints-based approaches to coaching and affordance theories were also borrowed from ecological psychology (Gibson, Bronfenbrenner & Ingold).

I have been working to synthesise my thinking into a framework that I have been calling a Waysfinder (wayS plural).

At its heart, it enables a process of continuous orientation or ongoing situational assessment and sense-making of where we are, who we are, and where we fit in the current environment.

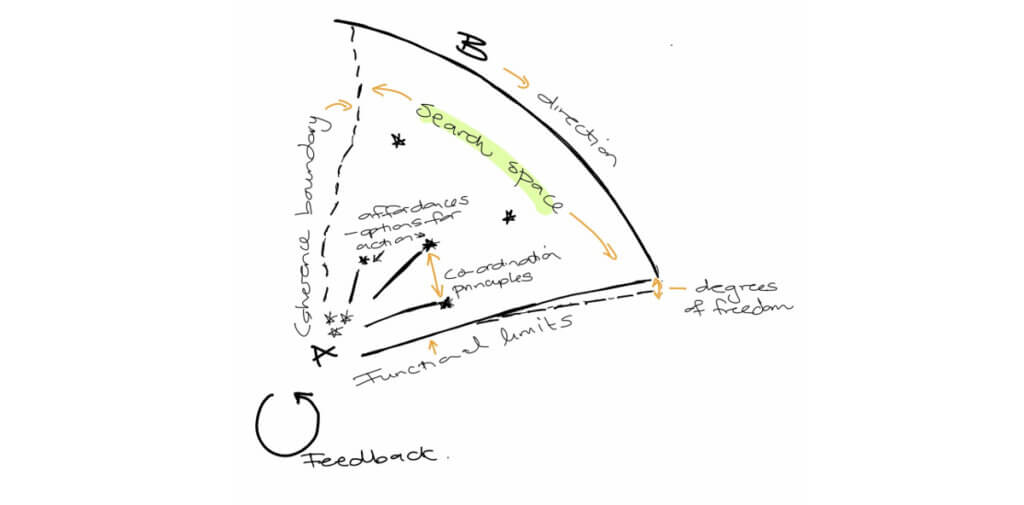

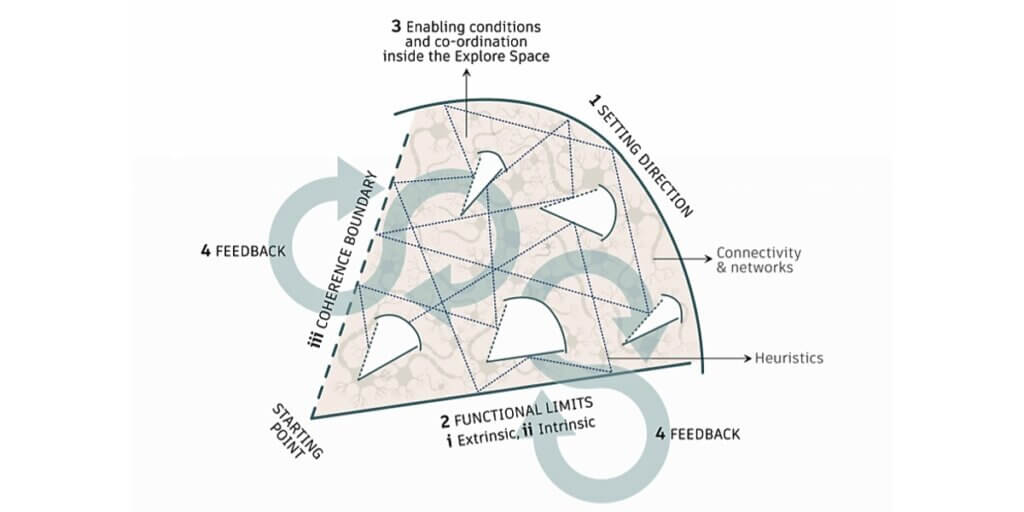

In addition to figuring out our current location(s) –position A in the picture– we also seek to identify potentialities from position A by asking the question, “What is possible from here?”

Knowing that our current position is dynamic, it becomes necessary to continuously orient ourselves to determine a potential movement to the next possible state.

This possible state is perceived and not definitive. It must be understood that the possible state that is being sought is not necessarily the end result. There are too many conditions and constraints that are ever-changing for any one person to predict the end result. In fact, an end result is rarely achieved, and we have to question the stability and resilience of any outcome.

The Waysfinder provides a scaffold that enables new thinking and practice, not a series of linear steps. It is made up of a combination of various types of constraints and wayfinding practices that collectively create a coherent adaptive space or search field.

From the beginning I visualized a cone (affectionately known by some of my clients as Sonja’s Pie or Pizza-slice :)) whose elements have evolved over time.

Although the framework has strong theoretical underpinnings, it is meant to be practical and easy-to-use.

- It can be used by an individual to help think through a next season or career change.

- It can be used by a team, or by an entire organisation.

- It can be nested, i.e., there can be one “slice” for the organisation and then smaller “slices” within for different teams or business units.

- It could even exist on a higher level, e.g., for an industry or social movement.

In essence, it is useful for any context where a variety of independent entities are working towards a common vision or shared intent, but needs local autonomy to explore different aspects.

You can use the Waysfinder to assess your current state, i.e., you can check which of these aspects are in place, and where there are gaps. Or you can use it to design a systemic context from scratch. A friend of mine used it to create the starting conditions for a volunteer community, to ensure coherence and autonomy right from the start.

In the second part of this article, I will explore how WaysFinder creates a scaffold for exploration through four constraints as well as how to get started using the framework. Stay tuned!

I am Sonja Blignaut and these are my agile-thoughts

2021 © Johannesburg, SOUTH AFRICA by Sonja Blignaut

Sonja has been working in the field of applied complexity for over two decades. She is a sought-after sense-making partner, speaker, teacher, and writer.

In her twenty-year consulting career, Sonja has worked with many blue-chip companies as well as not-for-profit and research organisations.

Founder and managing director of More Beyond, and co-founding partner in Sensemaking Partner and ComplexityFit.

Sonja is based in South Africa, arguably one of the best places in the world to learn about navigating complexity!

Was it interesting? Share it with others!