5 . Are We Asking the Wrong Questions? (II)

The Magic of Jobs-to-be-Done

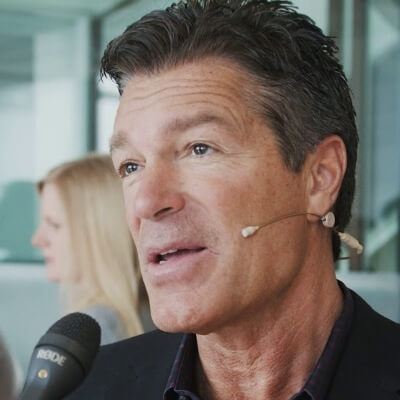

By Tony Ulwick

In the first part of this article, we explored some foundational ideas around Jobs-to-be-Done, the theory behind it, and nine tenets as the building blocks for making marketing more effective and innovation more predictable. Get surprised with this second part…

THE NINE TENENTS

- People buy products and services to get a “job” done.

- Jobs are functional—with emotional and social components.

- A Job-to-be-Done is stable over time.

- A Job-to-be-Done is solution agnostic.

- Success comes from making the job the unit of analysis, rather than the product or the customer.

- A deep understanding of the customer’s job makes marketing more effective — and innovation far more predictable.

- Innovation becomes predictable when “needs” are defined as the metrics customers use to measure success when getting the job done.

- People want products and services that will help them get a job done better and/or more cheaply.

- People seek out products and services that enable them to get the entire job done on a single platform.

Companies receive thousands of inputs from their customers every single day. They come from dozens of sources, including social media, the service desk, the sales team, customer advisory boards, and formal qualitative and quantitative research.

Companies are not lacking customer insights. If anything, they are overwhelmed with data. Despite these efforts, most companies do not fully understand their customers’ needs.

Why does it matter? Take a look at the organization.

- The marketing team needs to know the customer’s needs in order to define the company’s value proposition, segment markets, position products and services, and create marketing communications.

- The development team must know the customer’s needs so it can understand the strengths and weaknesses of the company’s products, decide what new features to add to existing products and what new products to create.

- The R&D department makes technology investments based on its understanding of customer needs.

- The sales team’s success depends on its ability to show customers that the company’s products meet their needs.

Company success depends on understanding the customer’s needs. And yet, amazing as it sounds, while company managers agree they must satisfy customer needs, there is no common understanding of what those needs are—and more alarming, rarely is there agreement on what a customer “need” even is.

Consequently, managers search through the information they have in hopes of discovering the nuggets of information that will lead them to success.

Unfortunately, it is nearly impossible to discover those nuggets when the statements they are looking for have yet to be defined.

That is a dire situation: trying to satisfy customers’ needs without a clear definition of what a need is. It is like trying to solve a word puzzle without knowing what a “word” is.

To overcome these issues, we use the jobs-to-be-done framework.

First, we define a market as a group of people and the “job” they are trying to get done. Dental hygienists (a group of people) who clean teeth (the job-to-be-done) and “parents who pass on life lessons to their children” constitute markets.

Next, we define a customer need as “a statement that tells the organization how customers measure value as they try to get a job done”. If you know how the customer measures value, you can create a product or service that will provide it—and you can do so in a measured, controlled way.

Because we build customer need statements around the job the customers are doing rather than a product or service they are using, they are stable for many years. While products and services related to listening to music (for example) evolve and change, the job-to-be-done (listening to music) stays stable throughout. Consequently, defining customer needs around the “job” makes these statements beneficial for long-term planning.

Moreover, since we include a measure of value (a metric) in these customer need statements, it is possible to see how various solutions compare in their ability to address them.

It is also possible to have customers prioritize them so the organization can determine which ones are most important and unmet.

These insights provide strategic direction to marketing, development, and R&D. To make sure these need statements can be prioritized without introducing error into the process, we ensure that they follow a strict, unvarying syntactical pattern, with no unnecessary words or phrases.

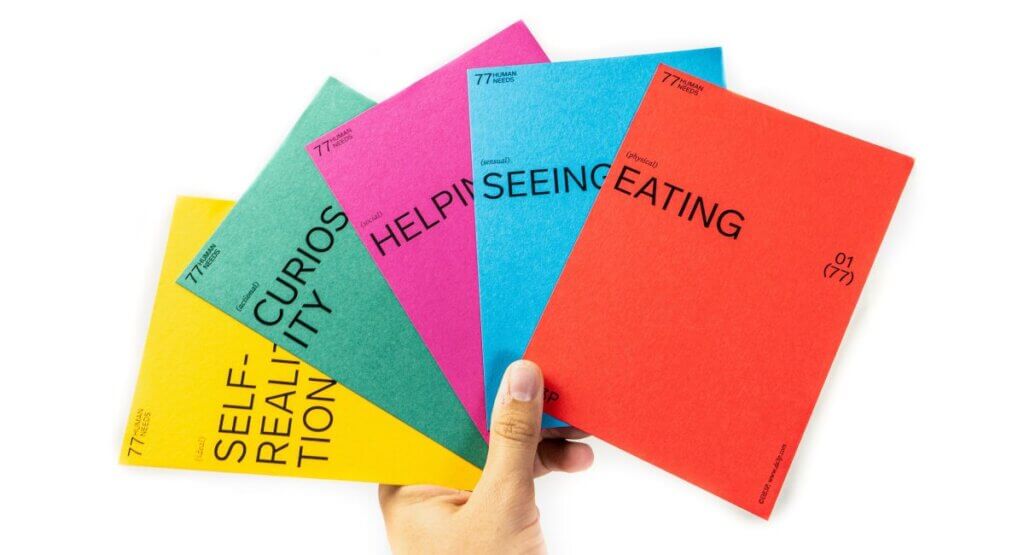

We call customer needs, formulated in the manner described above, “desired outcomes.”

Examples of desired outcomes while doing the job of listening to music include “minimize the time it takes to get the songs in the desired order for listening” and “minimize the likelihood that a song sounds distorted.”

For any given job-to-be-done, we often uncover between 50 and 150 desired outcomes. The key to a successful market or product strategy is knowledge of all the desired outcomes associated with a job-to-be-done, along with which segments of customers feel under—or overserved when it comes to those outcomes.

What impact does employing desired outcomes statements have?

Let’s say that out of 100 desired outcomes, you discover 15 that are unmet. What are the chances that your company would have randomly developed a product or service that addressed those 15 unmet outcomes if it had not known what those outcomes were? Pretty slim!

However, once everybody in the organization knows precisely what those 15 unmet outcomes are, all company resources can be aligned to address them—resulting in the systematic and predictable creation of customer value.

Jobs-To-Be-Done Examples

Over the years we have developed a set of rules that we follow to define the job correctly. Here are three of the dozen or so rules we use to get it right along with some jobs-to-be-done examples:

- We think about the job from the customer’s perspective, not the company’s one.

For example, a company that supplies herbicides to farmers may conclude that growers (the job executors) are trying to “kill weeds”, while the growers might say the job-to-be-done is to “prevent weeds from impacting crop yields”. To avoid this mistake, do not ask “what job are people hiring my product for”, rather ask, “what job is the customer trying to get done”.

Because customers often cobble together many solutions to try and get the entire job done, the answers to these two questions are often very different. We see many jobs-to-be-done examples in the blogosphere that get this wrong.

- We think big—to encompass the entire job, not just a piece of it.

A narrow focus will hurt a company because customers are looking for products and services that help them get the entire job done better.

For example, a company could focus on helping a grower “prevent weeds from impacting crop yields”, but they may want to consider helping them get the entire job done, which is to “grow a crop”. Customers do not want to have to cobble lots of incompatible solutions together to try and get the entire job done. They prefer to get the entire job done on a single platform.

- We define a market around a functional job, not the emotional goals that accompany it.

A company that offers a product that “prevents people from getting lost when driving” would do themselves a disservice to conclude that their customers are hiring their product to “achieve peace of mind”.

A focus on “peace of mind” will not deliver the insight that’s needed to better prevent people from getting lost. Knowing the customers’ accompanying emotional jobs is helpful, of course, but only when it comes to positioning and messaging, not innovation. Once again, we see many jobs-to-be-done examples offered in the blogosphere that miss this point.

Common Mistakes When Getting Started

“People don’t want a quarter-inch drill. They want a quarter-inch hole.”

This quote, which was made popular by Theodore Levitt, forms the foundation for Jobs-to-be-Done Theory: the notion that people buy products (like drills) to get a “job” done (e.g., create a quarter-inch hole). Sounds simple enough — companies are in business to create products and services that help customers get a job done.

Jobs-to-be-Done Theory goes on to say that a deep understanding of the job the customer is trying to get done will reveal unique insights that can make innovation more predictable, which is proven to be true. But exactly what customer and what job is it that a company should study?

In Levitt’s statement he implies that the job to study is the job of creating a quarter-inch hole.

But what if, as a researcher, you notice that people are creating the quarter-inch hole because they are trying to hang a framed picture on the wall? And they are hanging the picture on the wall because they want to create an attractive workspace? And they want to create an attractive workspace because they want to be successful in their profession? People may be trying to get all these jobs done, so which job should be the unit of analysis? What is the correct level of abstraction?

As a researcher you may also decide to talk with buyers and users of drills. In doing so you may discover very different sets of customer needs. Then the question becomes, “Which customer should be the focal point for data collection and innovation?”

You can see from Levitt’s example that defining the customer and the customer’s job-to-be-done can quickly take you down a rabbit hole if you fail to consider two very important factors:

- The customer’s job-to-be-done that is pertinent to a company is dependent on that company’s business objectives.

While a customer may be trying to get a variety of jobs done, a company may have a mission, the capabilities or the desire to address only one of them. This is a market selection decision.

- The user of a product is the only person capable of providing the inputs needed for product innovation.

Buyers, in many cases, are not users and while they can help you understand the buyer’s journey, they are not qualified to speak about the user’s core functional job.

These factors form the foundation for advice to avoid the two most common mistakes companies make when starting to apply Jobs-to-be-Done thinking in their organization.

01

Do not ignore the company’s business objectives

Let’s say, for example, that you are a drill manufacturer, and you are trying to improve your existing products or replace (disrupt) them with new products that create holes. In this case, studying the job of “hanging a picture on the wall” or “creating an attractive work space” is not going to help you.

Given that your company makes drills and wants to continue to make drills or competing products, you would need to study the job of “creating a hole.” Consequently, you would interview users of competing products that are being used to create a hole, e.g., a hand drill, electric drill, a hole punch, a hammer/nail, etc.

With a deep understanding of all the metrics customers are using to measure success when creating a hole (their desired outcomes) and new insight into which outcomes are under/overserved, you could then:

- Conceptualize new features that would improve your existing products, and

- Conceptualize all-together new products that could disrupt or complement your existing offerings

On the other hand, if you are a frame/hardware manufacturer, and you are trying to improve your existing products or replace (disrupt) them with new picture hanging products, studying the job of “being successful in my profession” or “creating a quarter inch hole” is not going to help you.

As a frame/hardware manufacturer, you would need to study the job of “hanging a picture on a wall.” Consequently, you would interview users of all competing products that are being used to hang a picture on a wall, e.g., wires, anchoring systems, etc.

It is important to note that even if the frame/hardware manufacturer created a new frame that eliminated the need for drilling a hole in order to hang a picture, the market for drills will not disappear. People will continue to buy drills to make holes in many other contexts — and the drill maker will still need to study the job of creating a hole.

The beauty of the Outcome-Driven Innovation process is that it can be used to study any job at any level of abstraction — and optimized to address the business objectives of the company that is seeking to grow through innovation.

Keep in mind that a job-to-be-done can be an objective, a goal or a task, a problem to be solved, something to be avoided, or anything else that groups of people are trying to accomplish.

02

Do not confuse the buyer’s journey with the user’s job-to-be-done

A second common mistake that we see people make when attempting to apply Jobs-to-be-Done thinking is that they confuse the buyer’s job (and outcomes) with the user’s job (and outcomes).

The reason Jobs Theory is so powerful is that it enables a company to deeply understand the core functional job the customer is trying to get done when using the product. Studying the job-to-be-done reveals the metrics that people use to measure success when getting the job done and opportunities to get the job done better/more cheaply.

But here is the problem — in many cases, especially in B2B applications, the buyer of a product has little or no experience using the product to get the functional job done. But because the company has a relationship with the buyer, and not the user, researchers end up talking to buyers about their buying job (the buyer’s journey) and fail to obtain the insights required to understand the job that the user is trying to get done (the core functional job).

While studying the buyer’s job (journey) can lead to insights that help innovate the purchase process, the inputs collected about the buyer’s journey will not help to innovate the product itself — and thinking they will is a common mistake.

Avoiding these two common mistakes will go a long way in helping you get your Jobs-to-be-Done efforts off on the right foot.

Strategyn’s website contains the best source of information about Jobs-To-Be-Done: check it here!

I am Tony Ulwick and these are my agile-thoughts

2021 © Pompano Beach, Florida, UNITED STATES by Tony Ulwick

Tony Ulwick is the Founder and Chief Executive Officer of Strategyn. He is the pioneer of jobs-to-be-done theory and the inventor of Outcome-Driven Innovation.

His work has helped the world’s leading companies launch winning products and services with a success rate higher than the industry average.

His best-selling book, “What Customers Want,” and his articles in the Harvard Business Review and MIT Sloan Management Review have been cited in hundreds of publications. His work has defined a new era in customer-centric innovation.

Interesting, right? Share it!