5 . Thinking Globally

Think Twice When Constructing the Value Chain

TAKEAWAY

Global awareness means having the wherewithal to leverage partnership (and strategic gameplay) to attack the real problem and improve overall flow.

The consequences of a poorly optimized global system will still hurt regardless of whether the constraint is inside your organization.

By Ben Mosior

It is common to believe that a system performs its best when each of its parts are individually optimized, but we know the opposite to be true; any improvement at a non-bottleneck in a system is an illusion and may even worsen system performance.

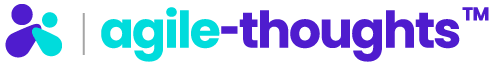

The Theory of Constraints differentiates these two views as local vs global thinking. To think locally is to make every part of a system perform its best, regardless of consequences affecting the whole. To think globally, however, is to focus improvement only on the bottleneck of the entire system, thus improving overall system performance.

If you believe in designing purposeful systems to deliver value, then global thinking is imperative to your success.

Systems Thinking for User Needs

Per Simon Wardley, purposeful systems fulfill the needs of their users. But in the messy reality we often find ourselves in, identifying users may not be a straightforward task.

Thinking Locally

If we start by thinking locally, our user may, for instance, be a customer who directly purchases our product. (It is a safe place to start, and we are already familiar with their needs.)

But if we zoom out a bit, we may realize that our success depends on their success. Perhaps they must use our product to provide value to others! Could it be naive to limit our awareness to only that initial customer?

Furthermore, for many in large organizations the most immediately accessible user is not the customer but someone in another department, or perhaps a local authority figure. What then? How likely are we to provide value to even our initial customer if we optimize first for internal needs?

Thinking Globally

For contrast, thinking globally means taking in a greater perspective — that of the overall system, which includes those who depend on us and those we depend on.

Who depends on our initial customer? And who depends on them? And who depends on them? And so on, until things are almost too intangible to imagine (a good place to stop).

It goes the other way, too. Who do we depend on? And who do they depend on? And so on (it’s turtles all the way down!).

Overall, we must picture the flow of value from its initial creation all the way to final delivery, across people, organizations, markets, and industries.

We are but a single component in a value chain that extends far above and below us.

So, to identify users, think globally. Your immediate customer still exists (and is important), but they might be only the next piece in a larger system. Their customer is your supercustomer, and each customer beyond is your further-removed supercustomer. We can trace the flow of value all the way to that final supracustomer (“supra-” meaning beyond limits) — the customer whose needs are so far away as to be completely intangible and therefore unhelpful to consider.

By orienting around the users of the entire system, up to but not beyond the level of intangibility (and diminishing returns of probable utility), we optimize in the interest of systemic success, also known as global thinking.

It is not that we focus only on the users nearest to us nor the ones furthest away; rather, in order to fulfill far-away user needs, we are forced to be aware of and cultivate capabilities needed to meet needs of all users along the way.

The Value Chain and Incentives

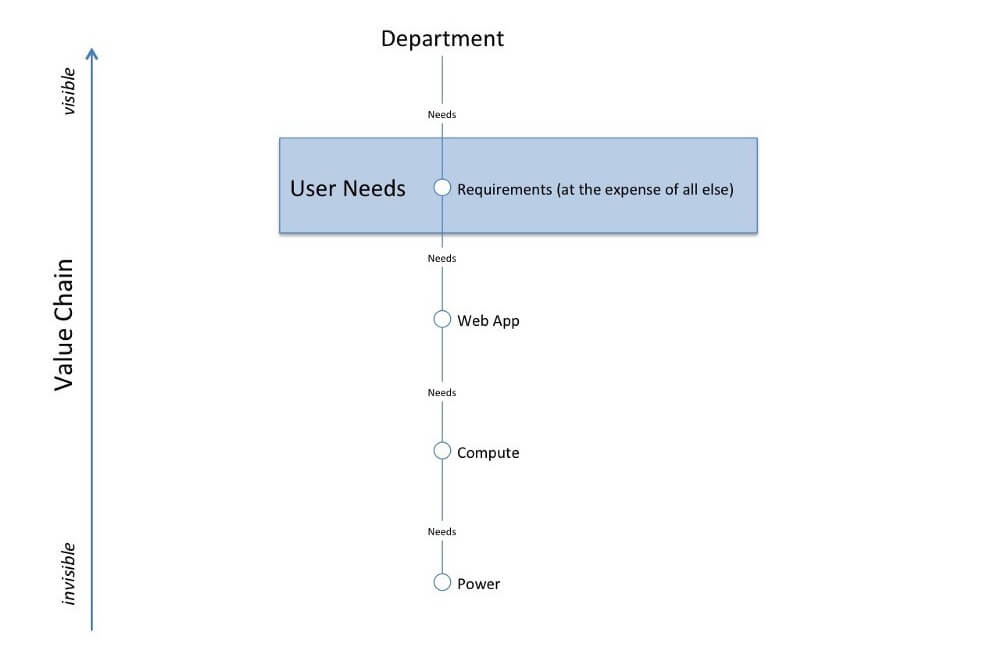

When we only think locally with respect to user needs, the incentives jump out to get us. Ask yourself, “for what do we optimize, at the expense of all else?”

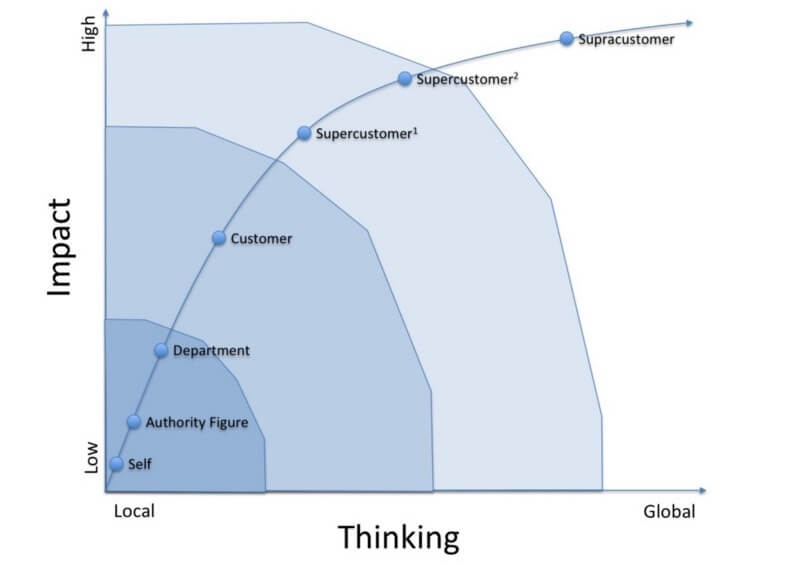

Imagine You are the User

For fun, we can begin with the concept of the self as the user. You may, for example, be building a product, but if psychological safety is low and organizational dysfunction is rampant, you may optimize for your own user need (survival) over all else. The value you create will be optimized to cover your ass and pay your bills — nothing more.

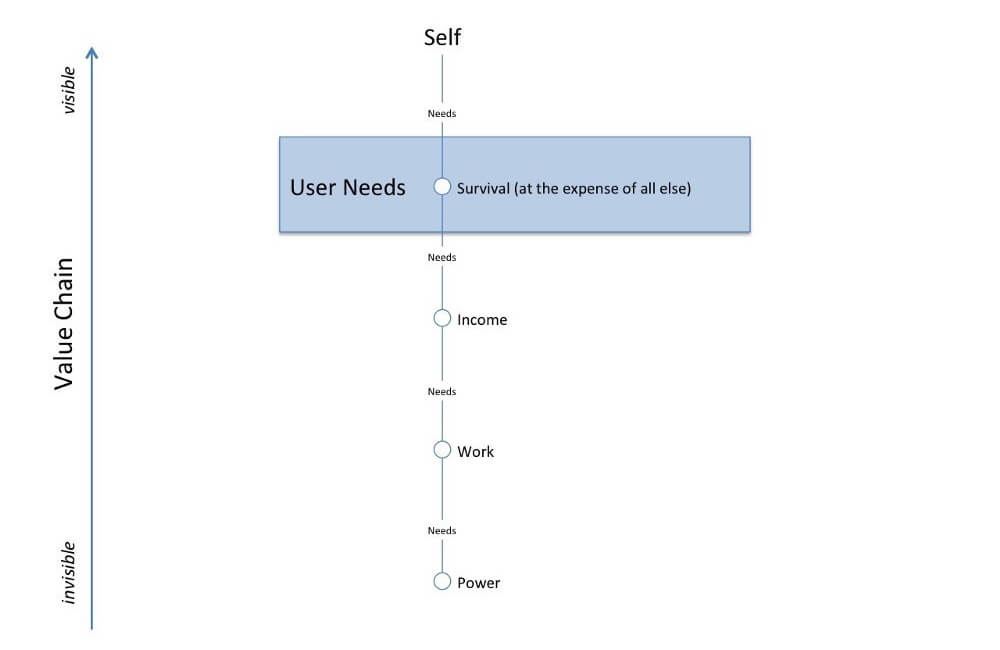

Your Boss is the User

Moving to a higher view, you may optimize for satisfaction of an authority figure (which may itself be tied to your own survival). However, just like self as the user, this approach drastically undermines the value being created by subordinating it to the satisfaction of an individual. You do what you’re told without connecting to any higher purpose.

The Product Department is the User

Moving along (though still in the realm of less-than-ideal organizational behavior), perhaps you optimize for internal requirements requested by another department. The thing you build (say, a web app) will resemble those requirements but may not adequately meet user needs. After all, the probability that the user needs will be perfectly translated and codified into exact feature sets is slim.

The road to ruin is paved with the best intentions of intermediaries, but hey at least you would be connecting to a slightly higher purpose: Keeping multiple people in another department from being upset with you… Yay!

Survival is still in the back of your mind, but you are mostly protected by the blessed CYA of bureaucratic process.

“But I adhered to all the requirements and submitted all the right forms,” you might say. “It’s not my fault we built something the customer doesn’t use or want!” (Though in my experience, you are lucky if you even come to realize that.)

The Customer is the User

Now we are back to zero, thinking at the same level as the people directly consuming the value we create. Instead of just building a simple “web app,” we might think in terms of our user’s needs, such as building a collaboration platform so that our customer can collect feedback from their users. The purpose is clear enough, and we can deliver value even though we are demonstrating relatively local thinking.

In some situations, it might be just fine if the story ends here. After all, so few get this far! (Really!)

For many others, the issue now is not so much doing the wrong thing but instead hyperoptimizing for the customer’s short-term needs. That means we miss the chance to enable success within the larger context of their users and customers, threatening our long-term success. After all, if they do not win, eventually we won’t win either.

The Customer’s Customer is also the User

Now our thinking is transitioning from local to global. We’ve begun to understand the larger context, particularly how the product we build fits into the larger scope of the world. In our example, our direct customer wants to collect feedback, but our supercustomer wants to exert influence. In view of the broader picture, our survival as a provider (and collectively, as a value chain) may be tied to how we consider and balance the user needs of both the influencer and the influenced.

It is not that we ignore the user needs of the lower-level components. In order to exert influence, the user needs related to gathering feedback still need to be fulfilled. The key is to recognize that the low-level components are now considered necessary but not sufficient to accommodating the full context.

What About the Customer’s Customer’s Customer (and Beyond)?

There may be more users above the supercustomer (i.e., other supercustomers) and corresponding understanding to build, but at a certain point the usefulness of the greater perspective begins to expire (or at least become more of an academic exercise). The supracustomer (again, “supra-” meaning beyond limits) might be, for example, as far away as “society” itself.

So, what are society’s user needs in relation to what we do? In this example, if society demands “progress,” is that something we can design through our fulfillment of influence, feedback, or other activities?

It is possible, but it might also be too far away to understand how our work connects to it. That is okay!

We may decide to take one step back from the edge, returning to the realm of activities more easily understood. We stretched our understanding to the limits, and now we know the system is not limited to just our product but is part of a long value chain of interconnected components.

Now what?

Global awareness does not magically solve all our problems, but it does mean we have a more complete perspective about the impact of our actions on the value we ultimately create.

From here, it might make sense to identify all the different users and user needs and then create a Wardley Map from each perspective. Or it might be fine to stick with the cursory kind of diagrams included here detailing who depends on whom else.

The point of global thinking is to optimize for the whole system. The constraint on system-wide value may be within your product, or it is also possible that it could be in the market itself or even another organization.

The key thing to remember is that the consequences of a poorly optimized global system will still hurt regardless of whether the constraint is inside your organization. So you may as well learn how it all fits together.

Think globally, see the big picture, and help others see the same.

I am Ben Mosior and these are my agile-thoughts

2021 © Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA by Ben Mosior

Ben Mosior is your friendly methodology whisperer, developing unknown methods into everyday tools and facilitating learning experiences for teams and communities.

His goal in work and life is to do his part to enable purposeful systems to flourish. Through Hired Thought, Ben shares decision-making and sensemaking approaches oriented around collective knowledge creation. To democratize access to strategic thinking methods, he operates LearnWardleyMapping.com and runs regular events to inform and uplift new practitioners.

Ben is also a contributor at the Yak Collective, a 300+ member indie alternative to the literary-industrial complex. In his spare time, he reads by a fire and does woodworking (poorly).